Post by MoMo on Oct 8, 2011 13:41:29 GMT -6

History

Classical

Throughout the classical period (defined here as the time from the first cities to the fall of Rome), the werewolf was generally viewed as a monstrous beast throughout Europe. The earliest verifiable werewolf tales we have from the period come from ancient Greece and Rome. In Greece, the stories of Lycaon being cursed by Zeus and of the Arcadians being able to turn into wolves by bathing in certain pools, are the primary sources. Both are likely tied to worship of Lykaian Zeus. The Roman sources include Petronius' Satyricon in which a dinner guest, Niceros, tells his tale. In the story, Niceros' traveling companion, a nameless soldier, pauses during their nocturnal trip to shed his clothes in a graveyard. There, he proceeds to urinate on his clothing before becoming a werewolf (in Niceros' words). Niceros fled immediately to avoid being eaten. The other major Roman source is Ovid's Metamorphoses in which the Greek story of Lycaon is retold. Both Petronius' and Ovid's accounts create, or recapitulate, a strong bond between lycanthropy and cannibalism.

Medieval

During the Middle Ages (defined here as lasting from the fall of Rome to 1400), the werewolf underwent a significant change in that the period saw the introduction of the "sympathetic" werewolf. Church leaders still saw werewolves as beasts, as did common folklore. In fact, the Church strongly denied the possibility of werewolves, declaring belief in the beasts to be blasphemy in Regino's Canon episcopi, c. 900. However, secular writers, notably Marie de France (12th century), began writing about werewolves that the audience was clearly meant to identify with. The two most famous of these "sympathetic" werewolves were Bisclavret (in Marie's lai of the same name) and Alphouns (of The Romance of William of Palerne). Many of these authors might have used werewolves as a covert means of discussing transubstantiation, which Church officials would not allow non-clergy to do openly. Carlo Ginzburg also identified the so-called benandante in northern Italy, as well as similar groups throughout eastern Europe, thought to change into werewolves to fight Satan's minions at the gates of Hell on a regular basis, usually one to twelve times a year (typically four times, at the seasonal changes). Needless to say, there was no single reigning common view of werewolves at this time. In most regions, views of werewolves varied depending on earlier beliefs and on views of normal wolves, which were extinct or nearly so in England at the time, for instance.

Early Modern (a.k.a. Renaissance)

The early modern period (1400-1650) saw common thoughts about werewolves become a duality. On one hand, most of the Continent viewed werewolves as savage beasts who had made a compact with Satan. The trials of Jean Grenier (France, 1603) and Stubbe Peeter (Germany, 1590) attest to this view. Most demonologists of the period spend at least a little time discussing werewolves, as do most witch hunters. Indeed, the werewolf and witch were often conflated in western Europe. On the other hand, in England and Scotland the werewolf was an academic, theoretical subject. Since the native wolf population had been exterminated, there were no wolf attacks, no threats from the animal. Therefore, werewolves were, presumably, also eradicated. Because of this lack of threat, virtually all British sources after 1500 refer to werewolves as people suffering from a form of psychosis and sought methods to treat the mental illness, said to be cause by excess choler or melancholy. Two excellent examples of this are James I's Daemonologie (non-fictional demon hunting guide) and John Webster's The Duchess of Malfi (play). This view did not stop the werewolf's popularity in England, though, as evidenced by the speed with which Continental werewolf trials were translated and printed on the island (usually within a year of the trial). Because of this popularity, Protestant church leaders adopted the werewolf as a symbol for Catholics, cannibalistic beasts bent on the destruction of the very society they hid within.

Early-20th Century

In the early part of the 20th century, most werewolf accounts appear in short stories and the early days of movie making. The most famous, of course, being Lon Chaney, Jr.'s Wolfman. This portrayal introduced the hybrid, humanoid wolf form and became the standard depiction of werewolves for decades. The period may also have introduced the idea of contracting lycanthropy from bites, something that appears in none of the earlier sources. The link between lycanthropic change and the phases of the moon also appears during this era. Previously, only Gervase of Tilbury considered said connection (and appears to have been ignored by his contemporaries).

Mid-20th to Early-21st Centuries

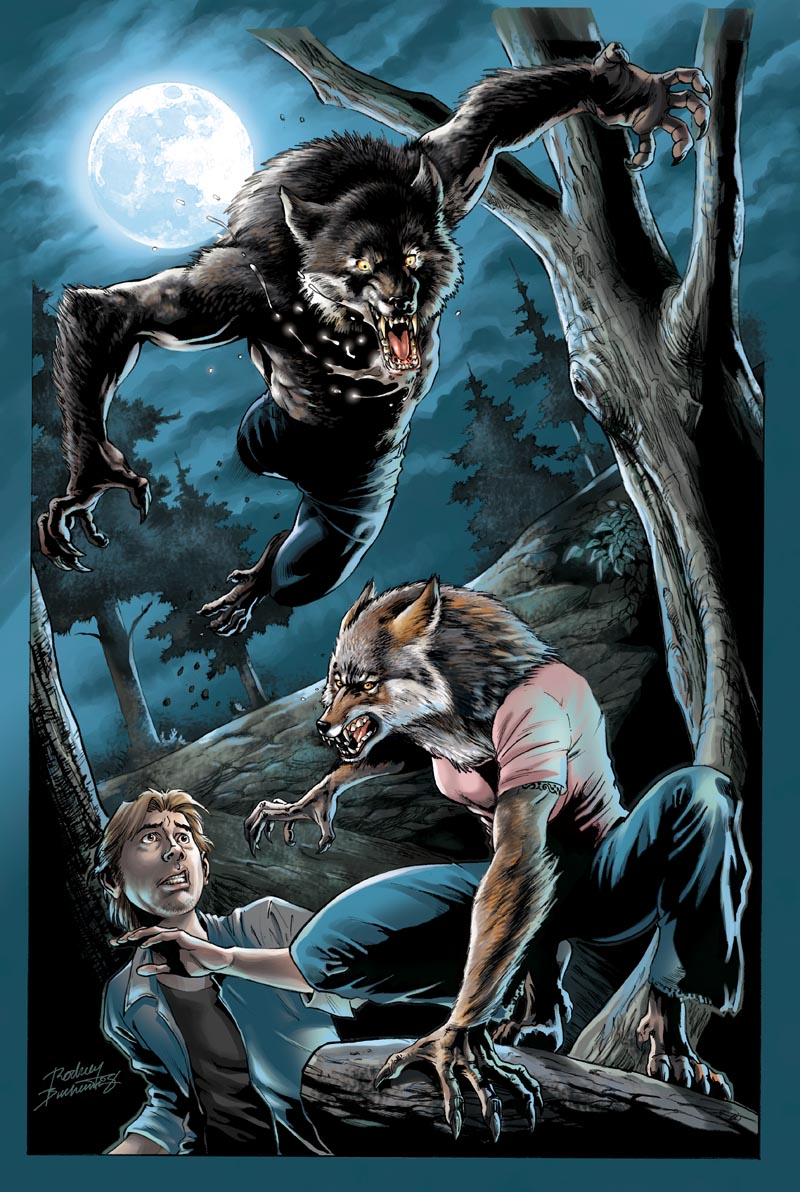

Currently, werewolves appear to be much like their medieval ancestors. They are used to evoke horror and sympathy in various forms (compare the Underworld franchise, American Werewolf in London, American Werewolf in Paris, and J. K. Rowling's Harry Potter series). Because of their interesting marginal and boundary crossing position, they have been employed to connect audiences to nature and discuss issues such as racism. It is in this period that we see the explosion of tales involving lycanthropy as disease, something particularly important to a world in which incurable diseases such as HIV/AIDS and related illnesses exist. We also see the introduction of werewolf-vampire animosity. Various reasons are given for the latter: Underworld's family strife, The World of Darkness' (oWoD) philosophical arguments, and Discworld's competition for the same prey (humans and, presumably, dwarfs).

Word Origin

The word werewolf is most likely to have come from the Old English words wer (or were) and wulf. Were translates into modern English as "man" and wulf is the ancestor to the modern English word "wolf."

Other sources state that the word came from the word warg-wolf. The word warg is old Norse for meaning outlaw or wolf and the wolf part is obviously modern English word wolf. (Needs citation/source, not present in this editor's ON dictionary.)

Other Names

garwulf - Norman French (also garvulf)

bisclavret - Breton (French/Celtic)

loup-garou - French

lycanthrope - Roman (from Lycaeon)

theriomorph - Greek

garou - White Wolf Publishing (shortened form of loup-garou)

lycan - modern film shortening of lycanthrope

Creation

The following are the most common methods by which werewolves are created. They are not the only methods, but the ones that appear across many cultures and historical periods.

Bathing - According to some legends, especially in Arcadia (a region of ancient Greece) and parts of southern France, individuals can become werewolves by bathing. These baths generally have to be done in special pools, during certain seasons or times of the month. This may be one origin of the full moon legend. Bathing can be seen in St. Augustine's discussion of lycanthropy (The City of God) and in Jennings' The Wolving Time (Scholastic Books).

Bite - Being bitten by a werewolf is said to turn the victim into a werewolf as well. This particular method first appears in the early twentieth century. No stories before 1700 C.E. involve people being bitten and turned into werewolves. One theory is that this method arises alongside views of lycanthropy as a metaphor for disease (including HIV/AIDS). The Underworld movies and J. K. Rowling's Harry Potter series brought this method back into the public eye.

Curse - Lycanthropy as a curse is easily the oldest method of becoming a werewolf. In most cursed werewolf stories, the victim is cured by the end of the story. Some early examples include: Lycaeon (cursed by Zeus), Alphouns (cursed by his stepmother in William of Palerne), the Ossory-Meath werewolves (cursed by Abbot Natalis or Saint Patrick in The History and Topography of Ireland) and King Gorlagon (cursed by his wife in "Arthur and Gorlagon").

Devil/Demon - Many early modern accounts of werewolves claimed demonic pacts or agreements with Satan as the source of shapeshifting power (most of which was deemed illusory rather than real change). Tied to magic/witchcraft, this method hit its height of popularity in the sixteenth century in France. It can be seen in accounts provided by Henri Boguet, Stubbe Peeter's trial, and Jean Grenier's trial.

Genetics - This is the werewolf who is simply able to change shape due to basic genetics. Surprisingly, this method pre-dates Darwin as Marie de France's Bisclavret (twelfth century) appears to be a genetic werewolf. Other examples include Terry Pratchett's Discworld werewolves and White Wolf's Garou (originally appearing in the Werewolf: the Apocalypse line).

Magic/Witchcraft - In the early modern period, witchcraft and werewolfism became intertwined. This method is also related to curses and demonic/Satanic involvement. In historical accounts, these werewolves used salves, ointments, or magical devices to change their form. Usually these were said to be provided by Satan. Modern versions include wizards/sorcerers using spells to change their shape. There is some debate about whether these individuals should be called werewolves.

Psychosis - The English and Scots in the early modern period began to question whether werewolves were really able to change shape (either in reality or via illusion). Since they'd driven wolves to extinction, they were safe from wolf attacks and therefore could approach the question academically. Thus, they began to see lycanthropy as a mental illness, usually an imbalance of melancholy or choler. British authors from King James I (1597) to Robert Bayfield (1663) to John Webster (see below) wrote of lycanthropy in this way.

Wolf Belt/Wolf Skin - Perhaps one of the earliest methods of effecting the transformation from man to wolf involved donning a wolf pelt or a belt made from a wolf skin. This method also became tied up with witchcraft in later accounts.

Mechanics

Once a person becomes a werewolf, what then? The following are some of the most common werewolf abilities and disabilities.

Cannibalism - Throughout their long history, werewolves have sporadically been associated with cannibalism (in this case, hunting and eating humans). This is true from Ovid's Lycaeon to Marie de France's garwulf to An American Werewolf in Paris. This does bring up the question of the nature of werewolf stories, though, since if the transformed werewolf is 100% wolf, is eating humans really cannibalistic?

Clothing - In most tales, werewolves have to either remove their clothing or lose it when they transform. Some werewolves need their clothing returned in order to resume their human shape (Bisclavret, for instance). This is typically a symbolic shedding of the trappings of society, including social rank/status and civilization in general.

Hybrid Form - Until at least the nineteenth century, werewolves possessed two forms: human and wolf. By the early twentieth century, they acquired a hybrid form, thanks in large part to the horror film industry. Some modern werewolves still only possess two forms - human and wolfman - but these are uncommon outside of Hollywood. Despite being a recent addition to the legends, the hybrid form has captured the imaginations of screen writers and the public. In fact, writers/directors have even gone so far as to ignore novel authors in their depictions of werewolves - a case in point is Rowling's Remus Lupin, who can be human or wolf in the books, but human or wolfman in the movies.

Mark of the Wolf - According to some legends, werewolves possess certain traits that expose their true nature in both human and wolf shape. Among these traits are hairy hands, unibrows, stubby or missing tails, snout shapes, and eye colors (vary by tradition). The existence of these traits is by no means universal, usually they only appear in a small cultural traditions covering a couple villages or a country for a given span of time.

Moon Change - The idea that werewolves can only change shape during the full moon is first advanced by Gervase of Tilbury in the early middle ages. This theory took several centuries to catch on, with most medieval and early modern authorities dismissing the idea. That said, some eastern and southern European traditions included other periodic forced changes. These were usually in line with seasonal changes (four times a year), every four months (three changes a year), or at certain festivals (harvest, sowing, midwinter). This theory can be easily connected to menstruation, in fact Pratchett created PLT (pre-lunar tension) which is nearly identical to PMS.

Rational Thought - Depending on the tradition, some werewolves are able to think like humans while transformed. Others become wolves both physically and mentally. Usually the tradition is determined by how the culture views werewolves. The former tend to see the transformed werewolf as basically human, whether morally good or bad. The others typically see werewolves as monstrous beasts. A few examples use both, such as Rowling's series in which werewolves are normally irrational, but can become rational with medication (Wolfsbane Potion).

Regeneration - The view that werewolves possess special healing powers is a modern addition to the legends. No pre-modern accounts ever imply that werewolves heal any faster or slower than normal humans.

Silver Weakness - As with regeneration, this is a modern addition to the legends. Pre-modern accounts cite no special weaknesses on the part of werewolves. On the other hand, most early accounts say or imply that werewolves can be killed just like any other living being.

Speech - In nearly every account of lycanthropy throughout western history, werewolves are unable to speak while in their wolf shape. Only a handful of exceptions occur, most notably Pratchett's werewolves who can create an approximation of human speech while transformed.

Sympathetic Wounds - Practically every werewolf account in history notes that wounds sustained in one shape transfer to the other(s). In fact, during the early modern werewolf hunts, sympathetic wounds were often cited as the surest sign that someone was a werewolf.

Wolfsbane - Like silver and regeneration, a lycanthropic allergy to wolfsbane seems to be a modern addition to the legends, and one that not many authors employ.

Cures

Only a handful of cures for lycanthropy/werewolfism exist in literature or historical sources.

Bathing - For those who transform by bathing in special pools, usually bathing in the same pool is required to change back to human form. Although this is not a cure as such, it can be seen as a temporary cure.

Conversion to Christianity - Traditionally, across Europe, convincing the werewolf to convert to Christianity can automatically and permanently cure the werewolf. Sometimes coming back to the Church (for those who use Satanic pacts) can work as well. This cure is especially popular among early medieval Christain authors for obvious reasons.

Removal of Curse - A simple removal of a curse can cure such werewolves. This can be as simple as returning the werewolf's clothes to an actual spell/ritual performed over the werewolf, as in William of Palerne. Sometimes, even though the potential for the curse being removed exists, the practicality is another story (see Lycaeon, since it is highly unlikely that Zeus will lift the curse).

Three Strikes - Related to conversion, some traditions claim that werewolves can be cured by striking them on the forehead three times. The striking item varies from region to region, but the most common are: a sword, a cross, a dagger, and holy water. Obviously, the sword and dagger are crucifix substitutes, being cruciform in shape. The number of strikes is important both in folklore (see the importance of threes in fairy tales, alchemy, magic traditions, and folklore) and in Christian doctrine (the Trinity of Father-Son-Holy Ghost/Spirit).